This is a picture of my copy of the Edge Books reissue of Tom Raworth’s Ace (2001). Initially printed in 1974 and reissued in 1977 and 2001, it was given to me years ago by poet and editor of Raworth’s selected poems, Miles Champion. It was Miles who first introduced me to Raworth’s work and seemed to have an endless stack of copies of Ace sitting around to put into receptive hands. It can’t really be made out in the photo, but the spine of the book is permanently rolled from the months (or maybe years) that I spent carrying the book in my back pocket.

For me, the book is deeply connected to the time that I spent reading it while on the F train on my way to and from work when I was living in New York. Maybe “reading” is too strong a word. At least in the years before I managed to hear a recording of Tom reading the work (on a cassette tape that hand been dubbed and redubbed like a recording of a Grateful Dead concert in the days before archive.org), I didn’t read the book so much as just spend time with it open in front of me. It took hearing Tom read it in his rapid fire enunciation for me to even start to understand what was going on. Reading the work at a breakneck pace, Tom elides the question of attention to the semantic meaning of the text, pulling the listener along with the current of his pace and rhythms.

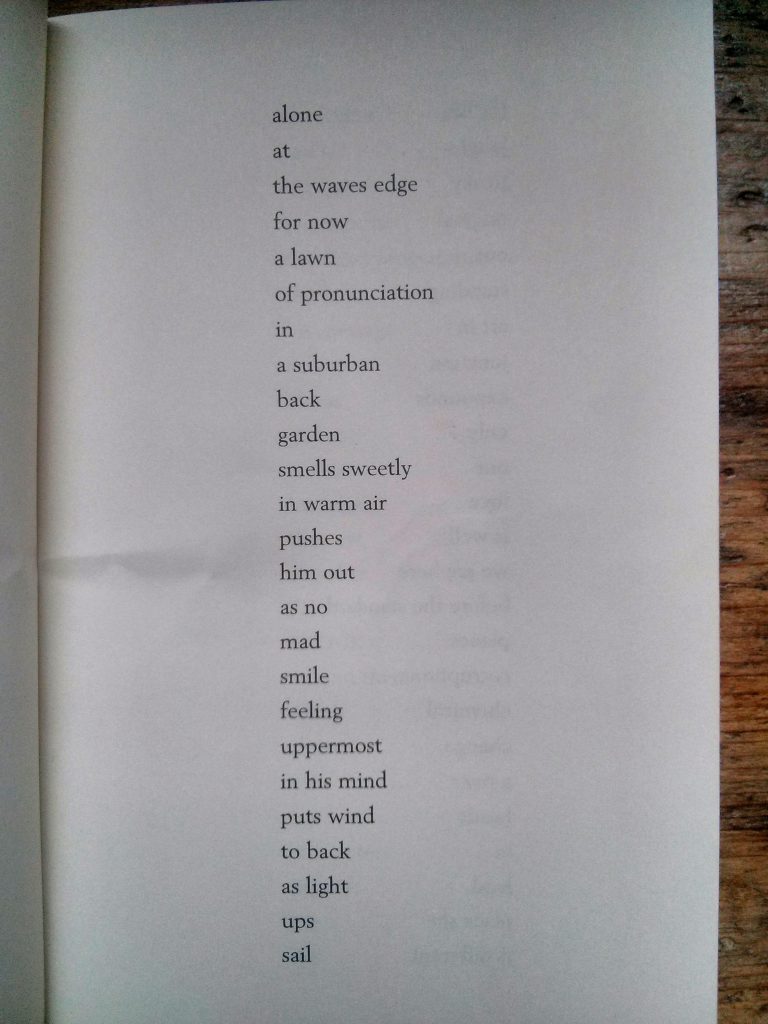

If you’re not familiar with it, Ace consists of mostly single or two word lines laid out in a slim column which runs down the middle of the page, with the connections between the lines kinetically sounding off with a crackling electricity between them. Here’s the text of one of its unnumbered pages:

groups

but list

who comes

beside

life

strange

friends

change

was

coldest

no

miserable

worship

mad

no

mad

lost

treachery

led to

shaking

hands

will

you use

it

regularly

Each line works as a pivot to the next, with the syntax of the entire 80 or so pages of the book-length work not lasting for much more than any pair of lines. Even with this, the whole poem coheres around the particular mental movement that the work creates, with the thematics (motion, thinking) engaged and repeated, resonating across the formal and sonic structuring.

At the time when I was first carrying the book around with me, I had no context for Raworth’s writing other than Ace, and the work held a certain kind of meaning as I read it on the train or while standing on the subway platform. Before hearing Raworth’s recording of it which affirmed the sonic and rhythmic anchor against which the book worked, I was left tossing about within the volume, looking for connections and themes that displayed themselves in multiple ways spread throughout the text.

In Ace, I found a book that offered another way to read. It invited scattered bursts of attention as much as a sustained reading. It offered something to me whether standing in a packed car in rush hour or waiting on a desolate platform at midnight. Reading a couple lines, glancing at a few pages, or just quickly skimming through a section were all modes of reading that offered something. The poem opened itself even if you just ran an eye down the strip of type like it was an abstract drawing or sculpture.

The book’s lightness allowed me to bring whatever I had at the time to it. The text that it presented to me wasn’t so much waiting there for me to read as it was waiting to be activated through an active and engaged reading.

I don’t want to think too much about what Tom wanted to get out of writing Ace, or what he hoped readers would see in it. I always think of his writing as being too generous and intent on the pleasures of reading and writing to worry about any kind of authorial or systematic intent. And in any event, when I was first exploring Ace, I couldn’t have known. All I knew of Raworth was this one slim volume which came to be inscribed in a particular way to a particular place and a particular time in my life. The book is to me what it is based on the contexts of my encounter with it.

Jon Dovey wrote here about the competing senses of the ambient in ambient literature and has written elsewhere (Dovey, 2016) about the push that ambient literature makes beyond location in its contextual engagements with readers. For me, Ace points in these same directions, but in a strikingly different way. In this, it offers a particular take on the idea of what ambient literature can be.

More than just being a particular experience of literature in place, Ace comes to me as exemplar of the varying kinds of attention that are possible in reading. Sure, in many ways the book is a linear work: the slim cut of the text down the page drives the purposive rhythms forward, but the syntax avoids any sustained meaningful linearity. You can pick up Ace at any point and still get so much out of it. You can skip lines, pages, or even entire sections and the book still works. In this, it is interactive without being tawdry or pandering. It does what it does but makes no demands other than an attention of some kind. Even without attending to the book, for days or years after reading, it’s still possible to carry the rhythm of the work with you. For me, this deep set experience of the book tied it to a particular time and place. Today, if I slip Ace (or any other similarly-sized book for that matter) into my back pocket, the connection is reinvigorated and all the attendant conditions come rushing back. Through my engagement with it, the stream of data that Ace presents has come to be contextually fixed.

Ace is distant from the locative or new media foundations of ambient literature, but to me it carries forward an important illustration of the sense of the ambient described by Ulrik Schmidt (2013). In drawing out the connections found in the ambient nature of ubiquitous computing, Schmidt says that “ubiquity dissolves the tension between more and less important parts, between figure and ground” (p. 177). What is ambient rests over and above other modes of experience. The variability of intention toward a text and the problematic of the dissolution of a reading subject are rendered as key elements in what might be an ambient experience of reading. The dissolution of the subject isn’t taken as prerequisite for the ambient experience, but the experience of ambience engages this problematic. The reader and the conditions of the reader become the central focus of ambient literature both in an immediate and lasting way.

Considered in such a way, ambient literature highlights the link between ontological and epistemic determinations, particularly when thought of in terms of the intra-active perspective of someone like Karen Barad (2007). Developed largely out of a particular reading of Niels Bohr and his approach to quantum physics, Barad’s perspective puts forward the idea that knowledge of a thing and the thing itself are produced through a performative engagement between the knower and the known. In its want for the contextual engagement of a reader, ambient literature seems to follow along with such a logic. It is instantiated in its enactment.

For me, coming to know what Ace was (and still is) a task of intra-action. Somewhere, on a long lost cassette which recorded a reading by Raworth, he talked about the connection between the acts of reading and writing. I can’t find the tape, but I remember him describing the way that writing was as much reading as it was writing — that the two were inextricably intertwined. Knowing what you are writing is an inevitable necessity of writing. Not being able to track down the context for what he was saying, I don’t know if this is exactly what Raworth meant, but for me, thinking of Ace, it seems right: Reading and writing are linked. As much as it is clear that you can’t write without reading, I’d say that at some ontological level, reading is not possible without the kind of active inscription of meaning that writing is normally taken to be. Reading (in general) is an interactive experience in which the text is encountered in a willful manner.

This sense of the ambient in which there is a willful opening up on the part of the author cuts at cross purposes to a different rendering of the ambient given by Malcolm McCullough (2013). In his Ambient Commons, McCullough offers an antidote to what he considers to be the challenges posed by the deluge of unanchored and abstracted information: our experiences of data flows should be tied to place and to the really-existing contexts which give the data their importance.

This is a difficult idea, particularly when the conditions of reading are thought to be dependent on the willful interpretation and engagement of the reader. Perhaps the model laid out in my own particular reading of Ace (and other similar texts) might provide some insight into how the management and curation of contemporary steams of data might be possible as they are given literary form.

In their failed encounter at the Goethe Institute in Paris in April of 1981, Hans-Georg Gadamer and Jacques Derrida clashed over the nature of the will to understand (Simon, 1989): should hermeneutics be guided by a good will to understand or a will to power to be understood? Should interpretation be guided by its reception of a field history as it is given or by the incision of your own understanding of it?

These questions are germane not only to reading texts, but to the formation of the very idea of ambient literature itself. Is ambient literature such a thing that will rise out of the occurrence of history, or must it be willed decisively forth? Time will tell.

Michael Marcinkowski

References

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Dovey, J. (2016). Ambient literature: Writing probability. In U. Ekman, J. D. Bolter, L. Diaz, M. Søndergaard, & M. Engberg (Eds.), Ubiquitous Computing, Complexity and Culture (pp. 141–154). New York, NY: Routledge.

McCullough, M. (2013). Ambient commons: Attention in the age of embodied information. London: The MIT Press.

Raworth, T. (2001). Ace. Washington, DC: Edge Books.

Schmidt, U. (2013). Ambience and ubiquity. In U. Ekman (Ed.), Throughout: Art and Culture Emerging with Ubiquitous Computing (pp. 176–187). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Simon, J. (1989). Good will to understand and the will to power: Remarks on an “improbable debate.” In D. P. Michelfelder & R. E. Palmer (Eds.) (pp. 162–175). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Comments are closed.