All spaces touched by humans will have their own encircling information stretching out over space and time. In our landscapes we have the traces of fossils, bones, cairns and other graveyards, architecture of all kinds, and the worked and reworked soil of farmlands, coal mines, gasworks, orchards, and forests. In our cultural lives we have oral histories, gossip, overheard conversations, interlocutors, artworks, adverts, announcements, preachers, signs, warnings, and portents. And to this patchwork we’ve added radiowaves, microwaves, wifi, Bluetooth, cellular data, transcontinental and transpacific and transatlantic internet cables, and the other trillion wires of ubiquitous computing, household homeostasis, and surveillance infrastructure.

There are always stories to be read and written around us, always stories in the air; to quote the movie Aliens: “they’re in the walls.”

To me, Ambient Literature is a literature which explicitly responds to this knowledge and recognises its distinctive character and intensification in our current moment. You’ll see many types of Ambient Literary works on this site that engage with these surrounding stories; today I want to imagine one more: digital literary works that pretend to find stories that “are always there waiting to be found,” even if those stories are wholly generated by the device, the software, and the actions of the reader.

Pokémon Go, which already feels like a dated reference, offers an example of this type (at least of this notion of ambience, if not of literature). For anyone that managed to avoid it, Pokémon Go lets you go out into the world with your phone in the hunt for creatures called Pokémon. When people go out with their phones “hunting for Pokémon,” the conceit of the app is that the Pokémon are out there waiting to be found rather than produced by the app and the actions of the walking player.

What’s interesting about Pokémon Go, in the context of Ambient Literature, is that the Pokémon and Pokéstops, made-up characters and places in the game, appear attached to real-world sites of interest: churches, graveyards, shops, historical sites, wherever people tend to congregate, wherever there’s already a story. In this way, a fictional kind of ambience, the notion that we’re constantly surrounded by pocket monsters waiting to be caught, reveals the very real ambience of your local environment’s ever-present stories of history and human action. You can’t help but trip over them.

One type of Ambient Literature, then, might do the same, in a more explicit, heightened, and non-monster oriented frame; it might perform an imagined, wholly fictitious ambience of “look at this story you discovered in the world” in order to reveal that you really are always-already surrounding by stories that are worth being attentive to, stories and information that already condition your every experience of your locality. This kind of play productively decentres our idea of text as emanating from a single object (a paper book) in a fixed location to be replaced, instead, by texts that already exist, out there, within an environment, waiting to be discovered through an object (our phones or tablets).

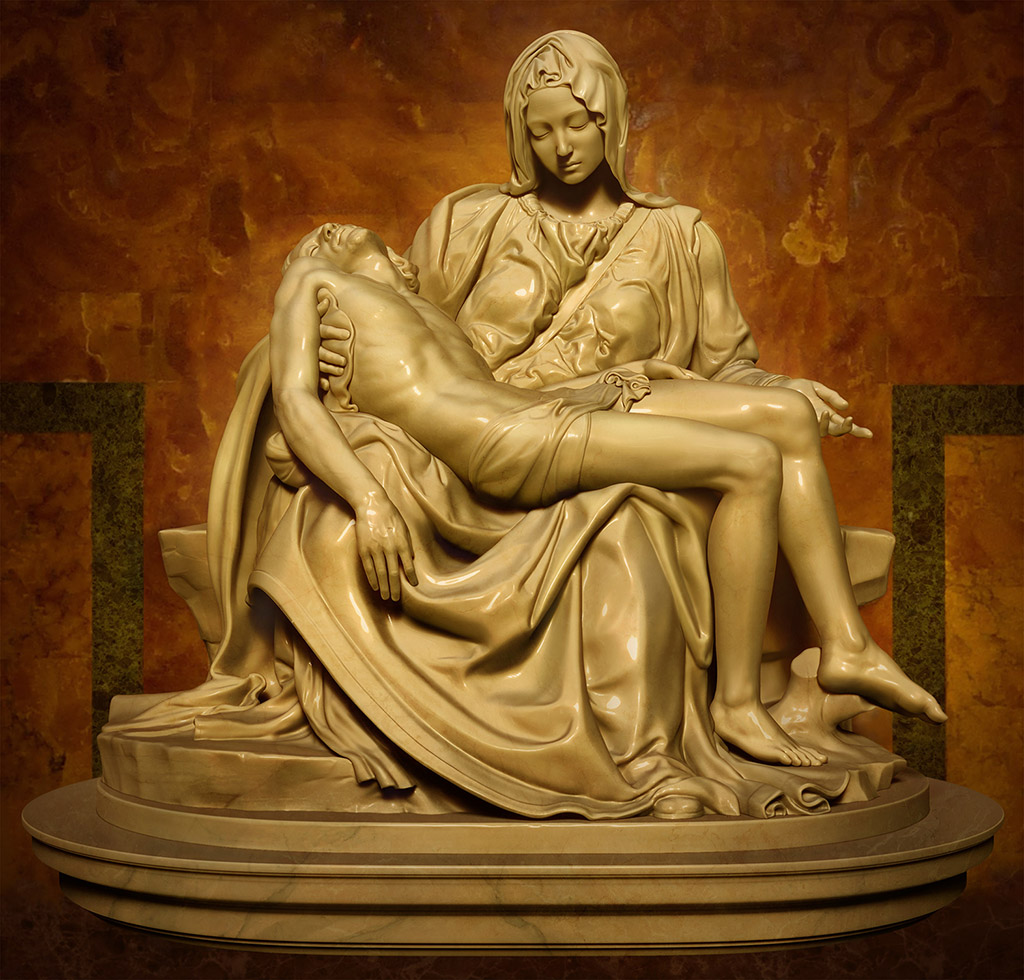

I’m reminded of what Werner Herzog calls “ecstatic truth.” In Michelangelo’s beautiful sculpture the Pieta, we see a young Mary, seemingly in her early 20s, cradling her dead son, the 33-year old Jesus. What’s strange is that the fabric of her clothing hides that she must be close to 7 feet tall to accommodate the man in her lap; her hands, too, are huge to cradle him as she does, but what we encounter seems wholly natural, graceful, and tragically tender.

This image has to be a lie; Jesus and Mary never looked like this, could never have been together like this, and never in these inhuman proportions. But the sensations of grief, the loss, the collapsing of time under the weight of experience, the perfection of the eternal mother somehow resolutely not being crushed beneath the abjection of her son – this is real. Mary is made beautiful, ineffable, and strong in her grief – the deeply personal and the divine become compressed as we bear witness to what all grieving parents must become if they are to endure.

The story of the Pieta, then, is a lie told perfectly to reveal a different truth that might otherwise prove inaccessible. And that’s why it’s kind of like Pokémon Go. . . . Both the Pieta and the pocket monsters lie to us about what’s out there in the world so that we might remember the truth of that world better. And this is something that works of Ambient Literature might do too.

— Matt Hayler

Comments are closed.