Under a fig-tree in a Milanese garden in the summer of 386 and in the throes of existential anguish, a prostrate and sobbing Aurelius Augustine — or, as we know him now, St Augustine — heard the voice of a child: “Pick up, and read, pick up and read” [tolle lege, tolle lege] At once my countenance changed. . . . I checked the flood of tears and stood up. I interpreted it solely as a divine command to me to open the book and read the first chapter I may find. . . . So I hurried back to the place that Alypius [Agustine’s companion] was sitting. There I had put down the book of the apostle [St Paul] when I got up. I seized it, opened it and in silence read the first passage on which my eyes lit: “Not in riots and drunken parties, not in eroticism…

The Printer’s Eye

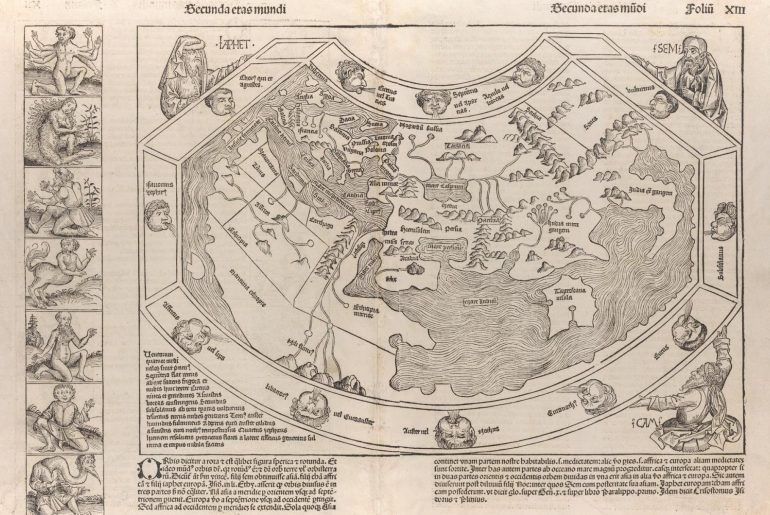

What do readers see? For most of the past half millennia, the answer has been straightforward: readers see rectangles, both visible and invisible. From the obvious orthogonality of the codex, the page-opening, and of course the page itself to the unseen boxes that frame the printed letters and lines, rectangularity is fundamental to our concept of the book as an object. Of course, rectangularity isn’t peculiar to print: manuscript books were rectangular too as is much of the man-made world, from bricks to beds, from doors to windows, from bank-cards to laptops. But the rectangle is integral to print because, for centuries, every page, every line, every word was made up of small rectangular pieces of type. These bookish rectangles are rarely considered by readers—apart, perhaps, when we are packing books in boxes or shelving them in bookcases—but they shape our reading practices. Our expectations about textual orientation, about where…

Lost in a Book

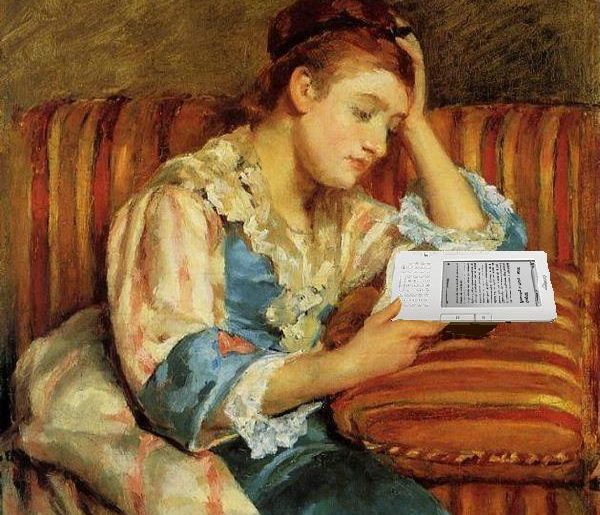

I’m a digital reader. So are you. But even though I’ve been reading texts on — off? — screens since the distant days of Ceefax and the ZX81, until this past summer I’d never actually read a book on a Kindle. I should clarify. I have had books downloaded on a Kindle app on my iPad for a few years now — mostly digital copies of texts I teach as that makes it easier to search and to copy-and-paste — and I did once use my iPad Kindle app to read most of a book about business finance. (It is, and was, a long story.) But that wasn’t really reading. What I mean is the kind of reading you reserve for stories: the reading you do curled up on the sofa on a wet Saturday afternoon or sprawled on a foreign beach; the reading that draws you in, that takes you away, that let’s…

Seeing the Crystal Goblet

The protagonist of Mark Haddon’s novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (2003) is a fifteen-year old, Christopher Boone, who discovers his neighbour’s dog has been killed. According to the back-blurb of the UK edition, he is described as having Asperger’s Syndrome, an identification that Haddon later regretted allowing; in the novel itself, Christopher refers only to his “Behavourial Problems” (59). Haddon represents Christopher’s world-view through a variety of non-verbal devices, including diagrams, drawings, mathematical formula, icons, and boldface. Less immediately obvious, perhaps, is the typeface itself: it’s sans-serif, which means it lacks the small hooks and extensions that you see in a typeface like Times New Roman. Sans-serif typefaces are usually used for display purposes, whether it’s the fire-exit, the next motorway junction, or the heading in a book. Serif typefaces, however, are conventionally used in newspapers and novels because they are meant to be easier…

Driving with Barthes

As a child, I read a lot in the back of cars. My parents, then recent immigrants to the UK, drove regularly across Northern Europe for family and work, and, unlike my sister, I was blessed with a constitution that allowed me to read in any sort of moving vehicle without feeling nauseous. Not every readerly child, of course, grows into a readerly academic, but the “use” of reading to while away the hours of a journey, or for that matter to while away the hours before that journey begins at the bus-stop or airport, is socially ubiquitous, even more so now with mobile phones. Reading while travelling, though, is itself relatively new. Despite the handful of readers in the past who startled their contemporaries with their ability (and desire) to read and walk at the same time—plus ça change—reading on the move needed to wait for the technologies of…