The Scottish surgeon, James Braid arguably gave hypnosis scientific credibility with the publication of his psychophysical research in 1855 [1]. His terms “neurypnology” and “neuro-hypnotism,” from Hypnos, the Greek god of sleep, aimed to distance the practice from the ‘animal mesmerism’ of Anton Mesmer and subsequent theatrical spectacles [2]. However, hypnosis, as Braid was aware, rather than a being a type of sleep, involves focused attention and suggestion, that can prime the subject for perceiving and imagining.

In The Principles of Psychology, William James [3] concludes that hypnotism involves focused attention coupled with the disassociation of background ideas. David Spiegel’s [4] discussion of recent neuroscience research suggests a similar interpretation, defining hypnosis as “. . . a state of highly focused attention coupled with reduced peripheral awareness.”

Evidence for the functional brain basis of a distinctive hypnotic “state” is debated, (as is the idea of brain states itself). Hoeft, et al. [5] claim that hypnosis results in, “. . . a top-down resetting of perceptual response . . .” and in experiments using fMRI, Müller et al. [6] argue that in highly suggestible individuals, hypnotic suggestions can affect visual auditory, somatosensory, and pain perception. Dillworth et al.’s [7] review of research in the neurophysiology of hypnosis and chronic pain reduction, concluded that clinical trials indicate the efficacy of hypnosis, however that this is not necessarily correlated with subjects’ susceptibility status.

“Highly suggestible” is a classification given to hypnosis subjects who have undergone assessment to establish their suitability for inclusion in empirical studies. There are a number of tests used by research centres, prominent among those is the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, developed by Weitzenhoffer and Hilgard in 1962 and modified by John F. Kihlstrom in 1996 [8]. The test takes the form of a carefully worded script delivered by the experimenter in which attention focusing exercises, are followed by suggestions about how the subject is feeling and invitations to deeply relax, fall sleepy. While it is also explained that it is not really sleep because listening to the experimenter’s voice will continue. When deep relaxation and eye closing has been established, further suggestions are made to feel and perceive, for example, to hear a mosquito and to act upon the suggestion by brushing it away.

John F. Kihlstrom [9], describes hypnosis as process involving social interaction and cognitive changes in “experience, thought and action.” Of particular interest to me in the context of situated literary experiences, are the methods for affecting perceptions, feelings and interpretation. While, as James [10] points out, our experience is only potentially subjective of objective, the possibility for suggestion to mediate our environment presents opportunities for active imagining and participation in story worlds. However, it is not necessary for participants of ambient literature to be deeply relaxed or on the point of sleep! Focused concentration and suggestion that directly and personally addresses the percipient, I propose, can extend the imaginative and affective power of storytelling towards perceiving and acting. This has been a focus of recent speculative research and ongoing speculative research.

The multi-stability of perceptual experience can prompt us to ask, how it is possible to have knowledge of the world and how is our our interpretation of events affected, within and below the level of our awareness? William James’ [11] radical empiricist philosophy explains that what things are known-as, are context dependent relations to ourselves, and that far from being fixed, are highly mutable.

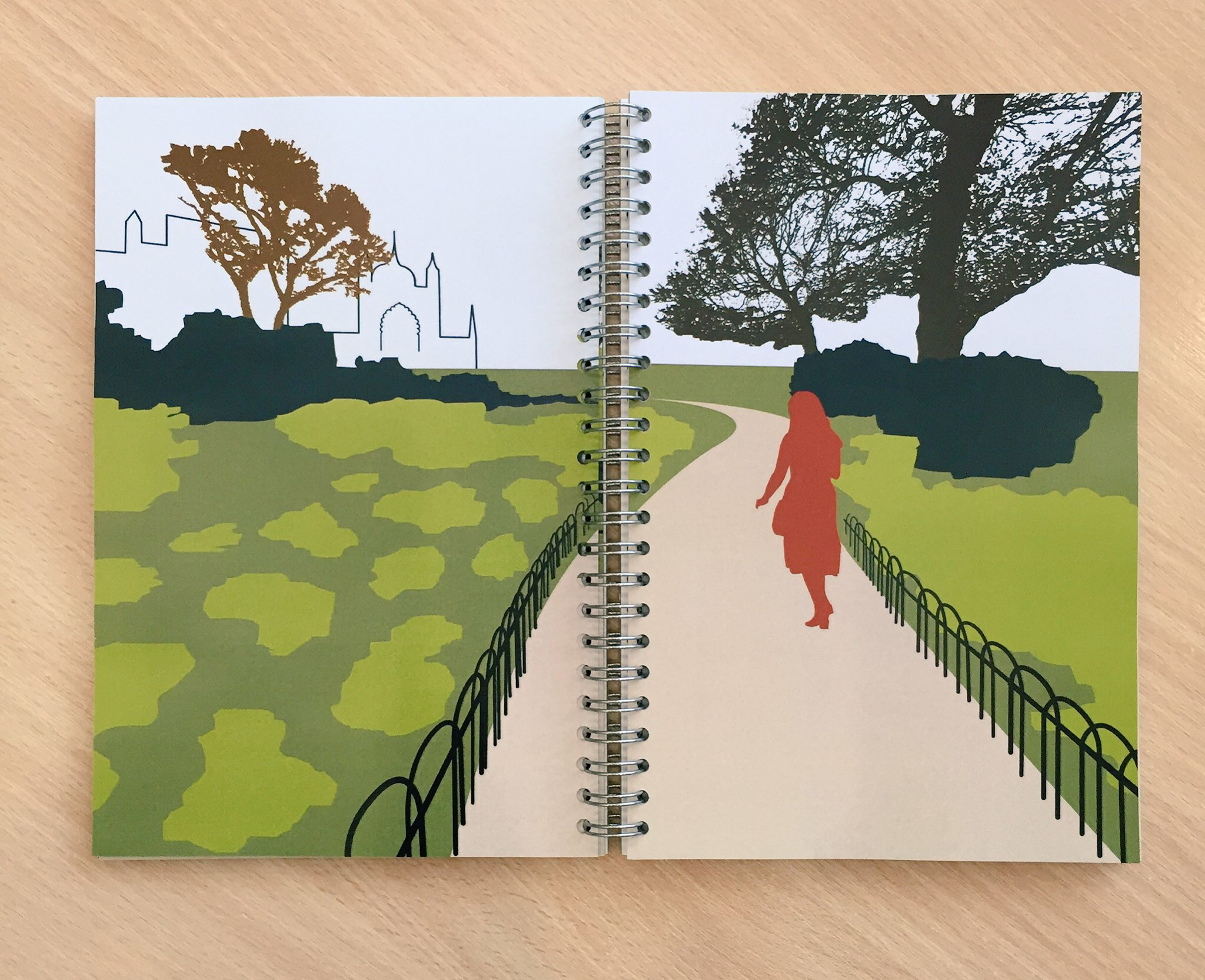

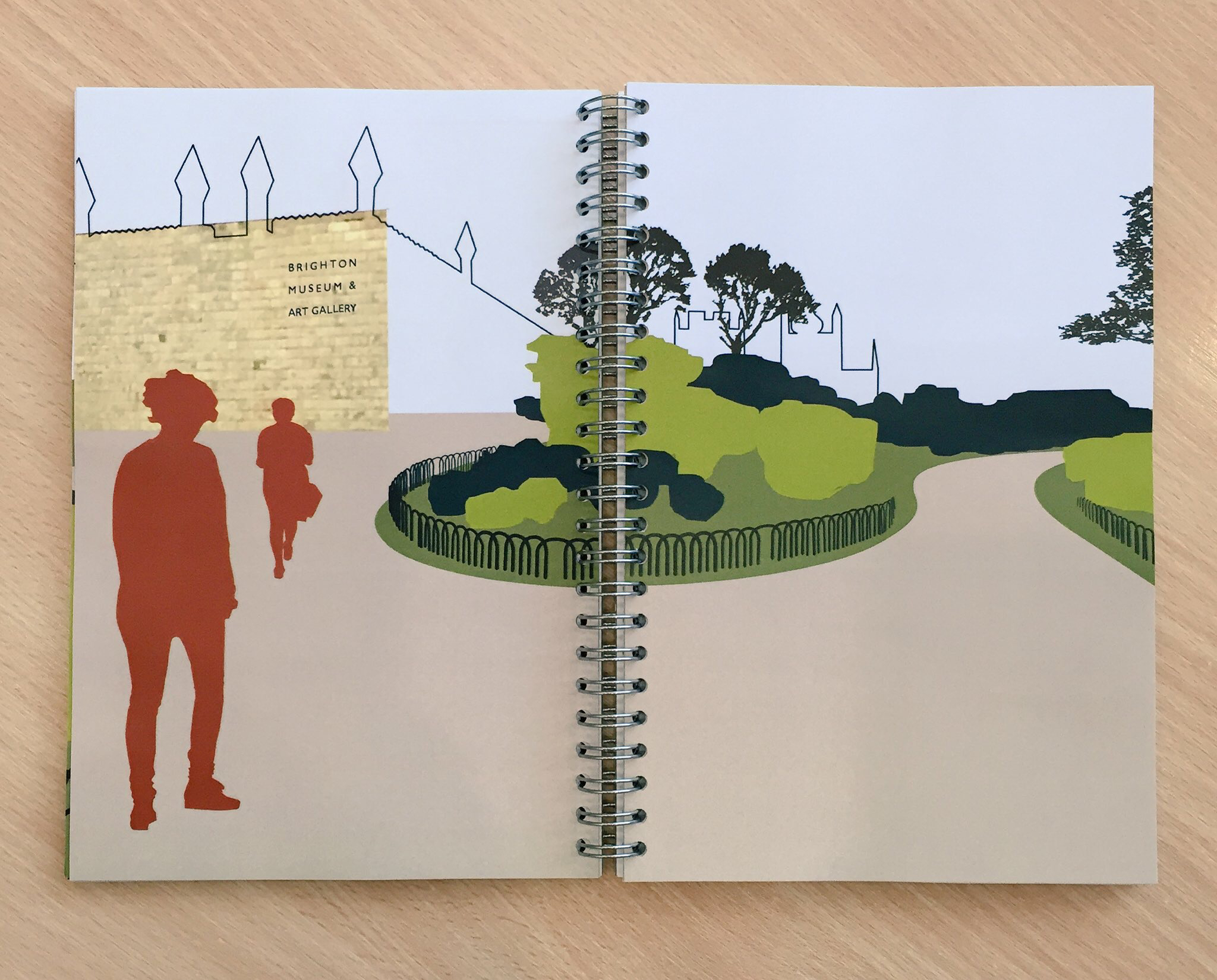

Building on a body of situated narrative smartphone apps, developed with my collaborator James Brocklehurst, I have been working with guided imagining, using techniques from hypnotic induction [12] together with the practice of shamanic journeying [13] to devise the form and content of narrative. The result is an initial experiment, Journeyer’s Guidebook, an iOS iPhone app and accompanying illustrated book, that was showcased in September at DRHA2016 and the Brighton Digital Festival.

Journeyer’s Guidebook [14] takes the participant on two parallel guided experiences, one beginning at the Jubilee Library, a physical walk to the Pavilion Gardens, and the other an imagined walk through the medium of an illustrated book, read inside the library. The form of the shamanic journey begins with the axis mundi, the entry point in this world, and proceeds through the aural depiction of a tunnel, a liminal space that marks the boundary with another world. Arrival in the garden signifies the beginning of non-ordinary reality. The journeyer, addressed in the second person, is invited to explore the garden, via their own route, before enacting a personal divination ritual and a contemplation on interpreting its meaning. Both journeys are accompanied by binaural spatial sound that in the garden heightens the ambient sounds and is supplemented with tropical birds. Inside the library the sound depicts the illustrated world. The inside journey begins with attention focusing techniques directed towards the body and the page, whereas the outside journey directs the participant to towards noticing their relations to the environment. The participant retraces their steps back through the tunnel before embarking on the alternative journey.

Our usual process of development involves a number of iterations to really hone the ideas and their implementation. Journeyer’s Guidebook script, interaction, sound design, field recordings, native app development, illustrations and book production were developed over a period of four weeks — a fast turn around. The feedback so far has generally been positive, but as is usually the way, testing on the ground presents many possibilities for further development. One of the themes that emerged from the last Ambient Literature seminar was the topic of creating situated literary works that can be experienced in many similar locations. The challenge is to write the world of the story so it pertains to participant’s environment, perhaps not wherever they may be, but in types of places the participant might be able to access, irrespective of their continent. This requires a particular approach to writing and interaction design that has the potential to open up ambient literature to the broader publishing industry. The next version of Journeyer’s will be rewritten to begin exploring this direction. . . .

Emma Whittaker

References

[1] Braid, J. (1855). The Physiology of Fascination and the Critics Criticized. Grant, Manchester.

[2] Kihlstrom, J. (2012). ‘The Domain of Hypnosis Revisted’. In. F. Nash, M. R., Barnier, A. J. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis Theory, Research, and Practice (Oxford Library of Psychology). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 21

[3] James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology, vol. 2, New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 600

[4] Spiegel, D.(2012). ‘Intelligent Design, or Designed Intelligence, Hypnotizability as a Neurobiological Adaptation.’ In. F. Nash, M. R., Barnier, A. J. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis Theory, Research, and Practice (Oxford Library of Psychology). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 81

[5] Hoeft, F. Gabrieli, J. D, Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. Haas B. W., Bammer. R., Menon, V., Spiegel, D. (2012) ‘Functional Brain Basis of Hypnotizability’ Archives of General Psychiatry Vol 69 (No. 10), October

[6] Müller, K., Bacht, K., Schramm, S., Seitz, R. J. (2012). ‘The facilitating effect of clinical hypnosis on motor imagery: An fMRI study’. Behavioural Brain Research, 231, 164-169. p.164

[7] Dillworth, T., Mendoza, M. E., & Jensen, M. P. (2012). Neurophysiology of pain and hypnosis for chronic pain. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 65–72. http://doi.org.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s13142-011-0084-5

[8] Weitzenhoffer, A. M. and Hilgard, E. R. (1996) Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Forms C (Modified by John F. Kihlstrom). Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. p. 8

[9] Kihlstrom, J. (2012). ‘The Domain of Hypnosis Revisted’. In. F. Nash, M. R., Barnier, A. J. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hypnosis Theory, Research, and Practice (Oxford Library of Psychology). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 23

[10] James, W. (1912). Essays in Radical Empiricism. New York: Longmans Green and Co. p. 141

[11] James, W. (1909) The Meaning of Truth. New York: Longmans Green and Co. pp.18-19

[12] Weitzenhoffer, A. M. and Hilgard, E. R. (1996) Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Forms C (Modified by John F. Kihlstrom). Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. p. 8

[13] Harner, M. (1992) The Way of the Shaman. Harper Collins pp. 68

[14] Whittaker, E. & Brocklehurst, J. (2016). Journeyer’s Guidebook. [iOS Application]. Retrieved from: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/journeyers-guidebook/id1146283679?mt=8

Comments are closed.