James Attlee, author of The Cartographer’s Confession, created for Ambient Literature, the AHRC funded research project investigating the locational and technological future of the book, in conversation with with Emma Whittaker, the project’s producer.

EW – What has been your process for writing The Cartographer’s Confession?

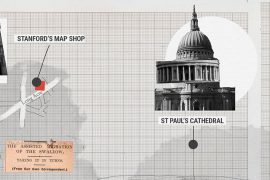

JA – It has been quite an organic one. I always knew I wanted the app to be set in a real place — London — and I wanted it to have a visceral connection with locations within the city. In part, The Cartographer’s Confession is about London itself, a city I love, but one so vast and unknowable I needed a unifying theme around which to build a coherent narrative. I found it in some photographic prints and negatives that came into my possession quite recently, street scenes taken in London in the late 1940s and early 1950s. They show a low-rise city scarred by war, in which St Paul’s Cathedral is one of the tallest buildings; a city where streets are almost devoid of traffic and the river is still a vital artery; where much day to day shopping is done in street markets populated by a colourful cast of characters. Here were my locations and my protagonists: the photographs opened a door into another world.

My story concerns a young boy and his mother who arrive in the city as refugees at the end of the second world war, who find a home among a community of market traders and who are then separated; it follows that boy’s attempt to manage both the city and his loss by becoming a cartographer and ultimately by confronting the part of his history that has caused him pain, resulting in a violent denouement. Against this narrative is set a non-fictional account of events in the winter of 1931. These two narratives, one fiction the other non-fiction, play against each other.

EW – What is the relation between the physical, fictional and imagined places in your literary app?

JA – Real locations have driven the development of the story in multiple ways. Sometimes I have gone to a place because I have imagined my characters going there and have then found visual or atmospheric details that suggest further events; at other times I arrived at locations because I have identified them from a photograph — the photographs act as a random selector of places within what De Quincey called the ‘mighty labyrinths’ of London.

The presence of the photographs sets up an interesting tension within the app. Participants can find themselves standing in the actual location where a photograph was taken in the late 1940s, looking at the photograph and also at the same view now, inevitably noticing the changes that have happened to it. This is little different to the experiences on offer in the form of fairly ubiquitous architectural apps or city guides that use AR (augmented reality) technology to overlay the past on the present. However, a participant in The Cartographer’s Confession might be hearing a fictional narrative set in that place in the 1950s or early 1960s or reading a letter written in the 1940s; the whole app is prefaced by a video, set in the present, in which the discovery of the materials we are accessing and the purpose of their assembly in the app is explained. In this sense the participant can be in four time zones at once, hopefully transported by the fictional drama they are hearing, yet still able to reach out and touch their physical surroundings. This sense of time travel is enhanced by the soundscapes created for the app by Jay Auborn, of dBs Music, which help locate the narrative both in terms of time and place. Further atmosphere is added through a soundtrack composed by the group The Night Sky.

EW – What has been your approach to writing this complex narrative that has multiple characters and locations and takes place across the twentieth century, moving between perspectives and time periods?

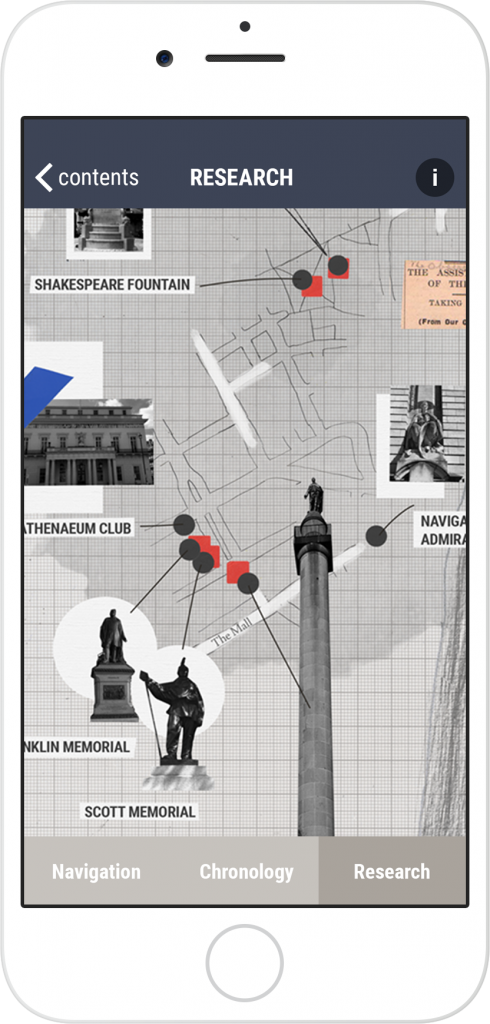

JA – The text is organized around three areas within the city, to which the participant travels to experience the story; this geographical movement is largely mirrored in a fictional movement through time, but the narrative is not strictly chronological: some of it occurs in flashback. We wanted to allow some freedom within the app for the participant to choose in which order they access the story within each geographical area, making the experience different each time and also accessible for different people, so it had to be written in a way that would allow that.

It is true the app exposes the user to a multitude of different voices and viewpoints coming via various media: film, cassette tapes, letters, newspaper articles, a radio broadcast, newspaper cuttings, narrator’s notes, as well as commissioned illustrations by Grace Attlee in collaboration with James Brocklehurst. I am aware this goes against some perceived wisdom that such complexity won’t work in the digital space, especially when the participant is being asked to listen to things in the street, to return to the app more than once, to spend as much time on it as they might reading a novella. In my view this underestimates the digital reader’s desire to be moved and challenged as much as readers have been in the past by printed books, as well as their ability to hold different strands of information in mind simultaneously. Literature has always been shaped by technology, from manuscript to printing press and beyond, to iPad and and Kindle; each development brings both new possibilities and new limitations and it has been a pleasure to explore these in relation to the app with the team working on this project.